Sunday, 21 July 2013

The World's End

Early on in ‘The World’s End’, the fictitious town of Newton Haven – the kind of depressingly generic English small town that’s not quaint or rural enough to be a village, nor close enough to the urban sprawl to consider itself a district of a city – is identified as being famous for having the first roundabout in Britain. (For the benefit of my non-UK based readers, that’s roundabout as in intersection, not the children’s ride.) It’s a curious thing about English towns that they clamour to boast about obscure or half-forgotten claims to fame, from the almost-interesting (West Auckland, County Durham: home of the first World Cup) to the blandly culinary (Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire: home of the pork pie) to the nobody-really-cares (Romford, Essex: home to the most lottery winners per capita in the UK).

Any English cinema-goer, on a single viewing, could probably name several dozen towns that Newton Haven reminds them of. And probably several hundred pubs evoked by the various watering-holes the five protagonists visit over the course of an increasingly bizarre, violent and hilariously fraught afternoon and evening. Because that’s another thing about being English: we love our pubs. For all that they’re becoming increasingly subsumed by chains (“Starbucking” is how Edgar Wright and Simon Pegg’s script puts it), or that the old-school spit ‘n’ sawdust working men’s pubs are as generic as the aforementioned chain establishments (a neat visual joke has the quintet blow the first joint as boring and roll up at the second declaring “this is more like it” only for a pull-back to reveal the interiors as identical), the English pub remains a nexus of social activity (good and bad), a retreat (a la the Winchester in ‘Shaun of the Dead’), and a place for youth to conduct an essential rite of passage whereby it pisses against the wall of manhood.

Two things you may have noticed about the above paragraphs: the use of “English”, not “British”; repeated references to masculinity. Because ‘The World’s End’ has two over-arching thematic concerns: what it means to be English; and how men interact/define themselves/fail to leave their youth or their past behind. In other words, take L.P. Hartley’s observation that “the past is a foreign country” and tip it on its head so that it’s the here and now that seems distinctly fucked up, add a couple of shots of Peckinpah’s rigorous and unflinching dissertations on masculinity, throw in some acerbic satire of the Monty Python variety, blend with ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ and ‘They Live’, and serve with a government health warning.

‘The World’s End’ is perhaps the most ruthless and unflinching satirical statement on the nature of Englishness that I’ve ever seen in mainstream cinema, and not just for the reasons mentioned above. The film’s coda – which it would be remiss to discuss just days after the film opened – serves up a commentary on the insular, belligerent, inherently racist, island-race mindset that has characterised the land of my birth throughout its classist, bloody and empirical history. It’s the heaviest-hitting piece of film-making Wright or Pegg have put their name to and it all but kills the laughs (albeit many of them uneasy) of the film’s earlier stretches.

You’ll already know the plot from the trailers: sad bastard Gary (Pegg), forty-something and still acting like the twat he was at eighteen (only at eighteen his mates mistook twathood for cool), convinces said mates – corporate lawyer Andrew (Nick Frost), civil engineer Steven (Paddy Consodine), upmarket car salesman Peter (Eddie Marsan) and estate agent Oliver (Martin Freeman) – to return to Newton Haven with him and complete the epic pub crawl they attempted at eighteen but never finished due to being eighteen and getting shitfaced very quickly. Gary refers to it, ad nauseum, as the best night of his life, but as the film progresses it becomes evident that not completing it has come to define his life inasmuch as it’s a personal failure he’s been unable to move on from.

Two decades and attendance at AA meetings notwithstanding, Gary is exactly the same person he was in his late teens. He dresses the same, talks the same, drives the same car. Everyone else has grown, matured(ish), changed. The first third or so of ‘The World’s End’ mines this dynamic for its humour. Pegg is unafraid to play Gary as essentially unlikeable. Few of his pals, for all that adulthood and responsibility have scrawled their signature, are that likeable either. Perhaps only Andrew and Steven emerge with any real decency. Regarding the latter, Nick Frost turns in the finest acting performance of his career, a nuanced and complex characterisation that allows Andrew to vacillate between poignantly sympathetic and fuckin’ badass when he cuts loose with two barstools and some bone-crunching WWF moves in one of the many hysterically staged and edited fight scenes.

And you’ll already know that things take an abrupt swerve into sci-fi territory. As the pub crawl – nicknamed the Golden Mile and encompassing twelve pubs (The First Post, The Old Familiar, The Famous Cock, The Cross Hands, The Good Companions, The Trusty Servant, The Mermaid, The Beehive, The King’s Head, The Hole in the Wall and The World’s End: there’s a play on each of the names and they all work on different levels, from the poundingly obvious to the sneakily subtle) – progresses, Gary and co. find themselves under threat from an otherworldly collective called The Network, and being too under the influence to drive and thereby make their escape, they’re forced to see the Golden Mile through to the bitter (or lager) end. En route, Gary and Andrew’s fractious friendship is further tested, and Gary and Steven’s teenage rivalry for the affections of Oliver’s sister Sam (Rosamund Pike) is revisited.

Wright and Frost begun their loosely connected “Cornetto trilogy” with the horror comedy ‘Shaun of the Dead’, which grew out of the twenty-something characters and situations of their London-based sitcom ‘Spaced’; ‘Hot Fuzz’ moved the focus to small town life and embraced the buddy movie/action thriller as its genre touchstone. ‘The World’s End’ takes the stoner/loser/smartarse protagonist of ‘Spaced’ and ‘Shaun of the Dead’, strips him of his loveability, transplants him slap into the heart of – and completely at odds with – the provincial outsider-unfriendly mindset of small town life pace ‘Hot Fuzz’, and ups the ante to cosmological stakes. How high? Imagine Iain M. Banks’s the Culture (and I rather think Wright and Frost had this in mind: there’s a very specific nod to Banks’s work in ‘Hot Fuzz’) squaring off against ‘Withnail and I’.

‘The World’s End’ will probably prove divisive. It kicks out ideas at such a rate of knots that audiences may come away bamboozled (I’ll openly admit that I was hesitant writing this review on just one viewing), and its final sequence goes into some pretty cynical (if still funny) territory. Its achievement, though, is an almost perfect synthesis of its predecessors while existing (and belligerently raising two fists to the universe) on its own terms.

Saturday, 20 July 2013

Despicable Me 2

At some point – probably while it was still playing in cinemas – someone took a look at the returns for ‘Despicable Me’ and gave the sequel the green light. At some point – probably after attending a kids’ party – someone sent out a one-word memo: “minions”. And thus ‘Despicable Me 2’ could easily have been “The Minion Show”. To certain degree, the epithet’s fair: the loony yellow thingies enjoy waaaaaaay more screen time in this outing, and they play a much greater part in the plot, but directors Pierre Coffin and Chris Renaud have a couple of aces up their sleeve to ensure that the minions don’t overwhelm.

The first is a beautiful reversal of Gru (Steve Carell)’s character arc from the original. As the film opens, he’s abandoned his crooked ways and has put Dr Nefario (Russell Brand) and the minions to work producing jams and preserves as part of a – shock, horror! – legitimate business plan; Nefario in particular is so incensed by legitimacy that he accepts a job offer elsewhere. Gru’s also being an attentive father to Margo (Miranda Cosgrove), Edith (Dana Gaier) and Agnes (Elsie Fisher). So far, so honest. Then he’s recruited – much against his will – by Silas Ramsbottom (Steve Coogan) of the Anti-Villain League to unmask a super-villain operating undercover from a mall. The crim-to-nice-guy transition of ‘Despicable Me’ is effectively flipped on its head as Gru has to re-embrace his old ways in order to get the job done.

The second is Kristen Wiig. After memorable work in an essentially nothing role (Miss Hattie) first time round, Coffin and Renaud reward her with the showier and infinitely more flamboyant role of Lucy Wilde, the agent despatched by Ramsbottom to first contact, and then work with, Gru. Lucy is wonderfully demented character and Wiig delivers in fine style.

All sharp suits, lipstick tazers and boundless energy, Lucy gives this film something absent from its predecessor: a romantic subplot. Where ‘Despicable Me’ traded on flashbacks to the dismissive attitude of Gru’s mother, the sequel depicts a playground humiliation that’s left Gru perennially nervous around women. His growing attraction to Lucy is frustrated by his well-meaning but annoying neighbour Jillian (Nasim Pedrad)’s attempts to set him up with her gum-chewing airhead friend Shannon (Kristen Schaal), and paralleled by Margo’s tentative romance with cocky teenager Antonio (Moises Arias), son of Mexican restaurant owner Eduardo (Benjamin Bratt) – one of Ramsbottom and Lucy’s chief suspects.

And on top of all this, someone or something is kidnapping the minions.

Plenty of material from ‘Despicable Me’ is revisited: the gloating villain in whom the heart of a lonely child still beats (the blithely indifferent mother is replaced by the matchmaking neighbour); Gru’s spectacularly non-conformist parenting skills (his attitude to his charges is a little less Dickensian this time around, but some of the entertainments he lays on for Agnes’s birthday party veer towards the don’t-try-this-at-home); Nefario’s frustration at Gru being sidetracked from proper old-fashioned villainy; Gru’s attempts to infiltrate the fortress-like lair of an even more devious villain than himself. But it’s all done so deftly, and woven around the development of all of its protagonists, that it never seems like ‘Despicable Me 2’ is a retread; indeed, it’s demonstrates the kind of organic progression from the first film that far more sequels should aspire to.

Moreover, it’s funnier, more inventive and boasts far more appealing animation. Lucy’s kidnapping of Gru and her journey to Ramsbottom’s undersea HQ melds ‘The Spy Who Loved Me’ and ‘Danger: Diabolik’ in fine, deadpan style. Eduardo’s hacienda recalls Sanchez’s Mexican hideaway in ‘Licence to Kill’, but with tacos instead of cocaine. The humour ranges from surprisingly subtle to utterly off-the-wall, reaching its most demented in a sequence where Gru, equipped with a Geiger counter type belt, prowls a suspect’s boutique, thrusting his crotch ‘Sexy and I Know It’ stylee at every object or surface that might yield a reading.

Pathos balances the humour nicely, as in Gru’s abrupt transition from Mr Positive when he senses he might have a chance with Lucy, to Mr Positively Depressed on thinking he might never see her again. If Margo’s brief but potent crush on Antonio will probably strike a chord with kids of a certain age group, Gru’s rollercoaster of emotions will almost certainly leave their parents nodding in sympathetic recognition. Elsewhere, Gru’s frustration at chickening out on making a phone call culminates in him pulling a flamethrower at the poor old instrument of telephonic communication: a poignant/slightly psychotic reminder that you’re never too old to get the jitters about asking somebody out immediately segues into pratfall heavy comedy as the minion equivalent of the fire brigade turn up to tackle the blaze.

Yup, it all comes back to the minions. They even hijack the end credits. And why not? They’re like a Greek chorus of cuteness, idiocy and abject incompetence wrapped up in one rib-tickling bundle. A yellow bundle.

Thursday, 18 July 2013

Despicable Me

Pierre Coffin and Chris Renaud’s out-of-nowhere hit starts with some horribly blocky animation and a handful of brilliant concepts. The horribly blocky animation depicts a vulgar American family on holiday in Egypt, the prototypically overweight scion of which accidentally discovers that the Great Pyramid of Giza is an inflatable replicable. The original has been stolen. The thief, who seems to have got clean away with it, is hailed in the media as a master criminal.

Leaving aside such questions as how the holy hell do you fence a pyramid? and where do you find a warehouse big enough to stow the thing while you puzzle over question one?, Coffin and Renaud (who should more like a firm of undertakers than purveyors of children’s entertainment) whisk us off to the suburbs of Anywhere, USA, and deal out – in quick succession – their handful of brilliant concepts.

We’re quickly introduced to the beak-nosed and European-accented Gru (voiced by Steve Carell), something of a master criminal himself. And boy is he cheesed off that someone else is getting the criminal genius kudos. He quickly hatches a plan – with the assistance of his sidekick, wheelchair bound inventor Dr Nefario (Russell Brand), and a troupe of yellow-skinned, helium-voiced, nonsense-jabbering minions – to steal the moon. This scheme, to be fair, makes a lot more sense than nicking a pyramid since the potentially catastrophic meteorological consequences make the moon an asset worthy of a high ransom demand.

Thus, the movie’s great concepts:

1) Gru, never mind his Bond villain stylee megalomania, has to go the bank like any other poor shmuck to beg for a loan in order to finance the operation.

2) Gru, never mind his indeterminate accent and decidedly un-American attitudes towards, well, everything, lives quietly in rickety old house on a street full of neatly trimmed gardens and picket fences and none of his squeaky clean neighbours even seem to notice that he has a freakin’ rocket powered car parked on the driveway. (Whether intended or not, it sets up an unspoken incongruity that the movie quietly trades on right till the closing credits.)

3) The minions.

I’m over 300 words into this review and I’ve been putting it off till now, but the minions are the reason ‘Despicable Me’ was a stupidly enormous hit, and the minions are the reason that ‘Despicable Me 2’ (of which more in a couple of days) was made at all, let alone ruled the box office since the second it opened and trampled ‘The Lone Ranger’ into the dust. Sorry, Steve Carell – entertaining vocal work, dude, but they could make ‘Despicable Me 3’ without Gru and just have the minions running around laughing at kiddie-friendly double entrendres for an hour and a half and it would net $100million in its opening weekend. Sorry, Gore Verbinski, Johnny Depp and Armie Hammer, but it’s hi-ho yellow as far as ticket sales are concerned.

Swinging back to the plot synopsis, the president of the Bank of Evil (check out the Corinthian columns leading up to the reception desk: a better visual comment on what banks do to people I have yet to see in a movie, animated or otherwise) reviews Gru’s borrowing-to-repayment history and bawls him out. With the scheme predicated upon the use of a “shrink” gun to render the moon transportable, the president gives Gru an ultimatum: acquire said technology, after which the loan request will be reconsidered.

Gru happily steals said item from a Eurasian military installation (I’m guessing North Korea, but this is a kid’s film and Sarcophagus and Renaud wisely keep the politics foggy) only to have it heisted from him by cocky up-and-coming young villain Vector (Jason Segel). Incensed, he plots to steal it back.

So far, so good. If Donald E Westlake’s Dortmunder had hung out with Ernest Stavro Blofeld and they’d watched the moon-in-the-puddle sequence from ‘Hobson’s Choice’ on replay while they dropped so much acid that they ended up hallucinating a room full of giggling yellow shortarses, ‘Despicable Me’ – up to this point – is probably what you’d get. Then Gru observes that the only outsiders Vector allows into his heavily armoured fortress are three orphan girls selling cookies. Gru instructs Nefario to build a group of cookie robots and sets about charming the hard-bitten matron of the orphanage, Miss Hattie (Kirsten Wiig), into allowing him to adopt the trio in question: wise-beyond-her-years Margo (Miranda Cosgrove), hipster-in-waiting Edith (Dana Gaier) and wide-eyed Agnes (Elsie Fisher).

What follows is toe-stubbingly predictable: grumpy Gru gradually bonds with the sisters to the point where he questions his lifestyle and becomes a better person. ‘Despicable Me’ could easily have not just dropped the ball but scored a classic own goal with it. And to be honest, the script never really shakes itself free of where the narrative arc forces itself towards.

Mercifully, Cremation and Renaud retain Gru’s non-paternal persona for longer than most kids’ films would have: the children’s initial living quarters consist of a patch of kitchen floor, three bowls and correspondence signs reading “food”, “water” and “pee pee and poo poo”; and Gru’s first attempts at putting his charges to bed yields my favourite exchange in the movie: “But I can’t sleep without a bedtime story” / “Then it is going to be very long night for you.” Nor does Gru fully abandon his klepto-lunar plans, even if – in the end – it’s Nefario who gives him the push when he hesitates.

Mercifully, too, the kids (with the exception of Agnes, who seems to be modelled on Boo from ‘Monsters, Inc’) avoid the usual pitfalls of cutesiness. Margo’s continual needling against Gru’s patriarchal parade of rules and regulations suggests the girl’s one step away from joining the Occupy movement, while Edith’s face-twisting scowl is something many a parent will recognise.

An effective contrast with Gru’s difficulty in engaging with the girls is the lifelong dismissive behaviour of his mother (Julie Andrews), revealed in a series of flashbacks. So many of cinema’s super-villains are motivated by arrogance, greed, revenge or lust for power. Gru just wants his mum to be proud of him.

Finally, though, ‘Despicable Me’ works because it’s breezily-paced, irreverent and always funny. Sad to say – I remember only a few years ago when a U- or PG-rated animation was virtually a guarantee of imaginative stories, glorious visuals and plenty of laughs – but of late there have been far too many animated films that have either coasted a moderately-fun-but-kind-of-pointless aesthetic (‘Wreck-It Ralph’) or been no fun whatsoever (‘Epic’). ‘Despicable Me’ – and its sequel, up next for review – buck the trend and deliver comedy, charm and entertainment in spades.

Sunday, 14 July 2013

THE AGITATION OF THE SMALL SCREEN: Steptoe and Son – Series 1

With the caveat that Dick Clement and Ian la Frenais’s ‘Porridge’ runs a very close second, it’s my humble opinion that Ray Simpson and Alan Galton’s ‘Steptoe and Son’ is the greatest sitcom in the history of British television. And the remarkable thing is that very often it isn’t funny at all. Very often, it’s cruel and embittered and almost painfully sad. Pathos and bathos have seldom been so enmeshed on the small screen.

Simpson and Galton never intended on writing a series, let alone eight seasons, two Christmas specials and two feature films. The vulgar, obstinate, determinedly working class Albert Steptoe (Wilfrid Brambell) and his loquacious, socially aspirant son Harold (Harry H. Corbett) were created for an episode of the BBC’s ‘Comedy Playhouse’ entitled The Offer. They had spent most of the 1950s working with the brilliant but prickly Tony Hancock on ‘Hancock’s Half Hour’ – the snob/pleb banter between Hancock and Sid James is something of a precursor to the Harold/Albert relationship – and weren’t looking to re-immerse themselves into sitcom writing. Tom Sloan, Head of Comedy at the BBC, had other ideas, and commissioned a series. Said series was produced in short order. The Offer was broadcast on British TV on 5 January 1962, with The Bird – the first episode of ‘Steptoe and Son’ series one proper – debuting on 14 June 1962.

The Offer, unlike many pilots which labour to establish character and setting, and whose aesthetics are often deviated from as resultant series find their own dynamic, presents the world of ‘Steptoe and Son’ fully formed. “You’ve held me back”, “you dirty old man”, the grubby expanse of the Steptoes’ yard, the abject poverty, Albert’s phlegmy low-class ruminations, Harold’s wordy wannabe middle class snobbery, the horse Hercules (beloved of Albert and hated by Harold), the antagonism/mutual dependency of the father-son relationship – it’s all there, perfectly encapsulated, in 30 minutes of grainy black and white.

Harold as a man of aspirations juxtaposed with set-in-his-ways Albert informs the five episodes of series one. In The Bird, Harold’s aspirations are romantic. A night on the town and the company of a young woman (the “bird” of the title) are what Harold sees as his reward for another thankless day at the rag ‘n’ bone trade. Albert protests that he’ll be lonely; tries to play the emotional blackmail card to keep his son at home. His maudlin soliloquy takes in his wife’s death and what he feels Harold owes him for the sacrifices made. “I had your education to think about,” he wheedles. “Not for long, though,” Harold shoots back; “I was on the cart at 12. Gawd, on the cart at twelve, in the army at 18 and back on the cart at 22. It’s all I’ve had.” Harold’s 37; a proximity to 40 that he harps on repeatedly. Albert’s eventual sabotage of Harold’s nascent relationship with the barely-seen but obviously middle class Roxanne (Valerie Bell) probably only presupposes what Harold would have achieved by himself in the long run, but it’s a nasty punchline to an episode already dripping in venom.

The Piano trades in slapstick humour more akin to Laurel and Hardy (indeed, the basic set up of a piano which requires removal from a penthouse suite unserviced by an elevator is immediately redolent of many a silent comedy) and is notable for relocating the action away from Oil Drum Lane (the fictional Shepherd’s Bush address of their yard). It also provides an insight into Harold’s contrariness. Hailed by a rich man (Brian Oulton) to remove the aforementioned piano – an unwelcome reminder of his ex-wife – Harold’s first impulse is to offer him the V-sign. Later, enticed up to the plush apartment with the promise of a grand piano that’s his to sell as long as he handles its removal – Harold the snob-in-waiting is revealed as acutely uncomfortable in the presence of the genuine article. Later still, though – returning with Albert to assist in shifting the piano – he becomes the parvenu again and repeatedly berates his father for his lack of culture.

The next two episodes – The Economist and The Diploma – see Harold trying to better himself professionally. A textbook on economics convinces him that bulk buying is a preferable option to the magpie-like acquisition of bits and pieces that characterises the rag ‘n’ bone trade. “Buying what?” Albert demands, contemptuously. “Doesn’t matter,” Harold responds, and therein lies his failure. 4,000 sets of uncollected false teeth come at a knock-down price, but selling them on proves harder than expected. The Economist ends in obvious fashion with Harold resolutely making the same mistake twice, but not before Simpson and Galton throw out some barbed comments about the political/economical climate of the day, particularly in relation to the Common Market. Harold imagines a tunnel beneath the English Channel (this 32 years before the Channel Tunnel actually opened) filled with foreigner rag ‘n’ bone carts. “English junk for the English,” he declares. Although contextualised, the line (with its nationalistic overtones) is one of many reminders of how different attitudes were back in the day.

The Diploma sees Harold studying to become a television engineer, all full of big talk about his capabilities with the new technology but undone in the end by basic incompetence. Simpson and Galton give us a nice parallel, however, with Albert’s return to driving the cart around London touting for business after so many years of forcing Harold to it while he stays inside and drinks tea (or more often gin). For all that Albert criticizes Harold for being “a rotten rag ‘n’ bone man”, he does no better himself. In fact, demonstrably worse. The Diploma isn’t the only ‘Steptoe and Son’ episode that trades on hubris – far from it – but it’s one of the show’s rare outings where the joke is equally on both protagonists.

The series ends with The Holiday, which boasts one extended comic set-piece involving Harold quite literally tearing through a bunch of holiday brochures while trying to decide which foreign resort is the likeliest location to pull birds. He finally settles on St Tropez (which both he and Albert pronounce “Saynt Trow-pezz”) as “they have it all on display there. Lets you see the goods at one glance. I’ve only got a fortnight, after all. Can’t afford to hang about.” Predictably, Albert doesn’t like the idea of Harold going off by himself – and abroad at that – when they could just go to Bognor, the Steptoe holiday destination since time immemorial. The humour flatlines to just plain sadness in the final scenes as Albert resorts to petulant measures to coerce Harold away from his exotic plans. It’s a brutally timed re-encapsulation of something the show, even in its more fanciful late-Sixties to early-Seventies second incarnation, never forget: ‘Steptoe and Son’ was a sitcom that didn’t always consider it necessary to pay lip service to the “com” bit.

Thursday, 11 July 2013

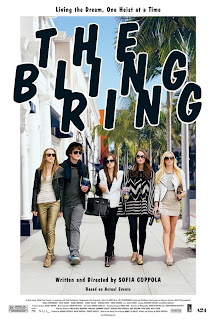

In brief: The Bling Ring

About a third of the way into 'The Bling Ring' - maybe less; it's a mercifully short film - a couple of over privileged teens decide to break into Paris Hilton's palatial LA residence. Entry is effected thanks to the cat-walk strutting heiress leaving a key under the door mat. The majority of viewers at the screening I attended groaned or face-palmed. Someone muttered, loudly, "No fucking way." Reading up on the background - yup, we're in "based on a true story" territory - it transpired this actually happened. This pair of designer-clotheshorse douchebags - later joined by various in-crowd buddies - were able repeatedly to break into the house of Hilton and rip off clothes and jewellery worth hundreds of thousands because Paris Hilton left a key under her door mat.

As the film progresses, more lamentable security lapses come to light, notably Audrina Partridge, Orlando Bloom, Rachel Bilson and Lindsay Lohan's inability to simply lock their doors before they leave the premises. Nor, it would seem, does anyone who lives in Hollywood

Thus the walk-in-marvel-at-the-designer-goods-walk-out-with-said-goods approach of our happy band of douchebags, all of whom had names and were played by people I'd never heard of before (except for Emma Watson who, to be perfectly honest with you, was the only reason I bothered with the film), but after a very short while I really didn't care and looking the cast up on IMDb hardly seems worth it for a 400 word review.

The big problem with 'The Bling Ring' is that, in depicting the actions of a bunch of vacuous nobodies obsessed with vacuous celebrities, the film becomes equally vacuous. This needn't have been the case, and a more satirical script and a sharper directorial approach could have made for an excoriating study of materialism and the dubious lure of celebrity culture. There are a few moments, particularly towards the end as the gang are unmasked and brought to trial, where writer/director Sofia Coppola comes close to engaging with the material with some degree of focus, but it's a case of too little too late. Whatever interest the last half hour generates, the first hour of 'The Bling Ring', with its desperately trendy soundtrack and oooh-look-at-me visuals, is little more than 'Hipster Douchebag: The Movie'.

(Oh, and to whoever designed the poster: it’s B&Es they’re pulling, not heists. Don’t try to dignify douchebaggery.)

Sunday, 7 July 2013

My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?

There’s an elephant in the room when it comes to ‘My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?’. It’s a big elephant with floppy ears and a trunk like a fire hose and somebody’s painted on the side of it, in garish pink letters, “this is, y’know, that Werner Herzog film produced by David Lynch that looks more like a David Lynch film than a Werner Herzog film”. If someone would be so kind as to take the elephant outside and pass me my elephant gun, maybe we can have an intelligent conversation.

Oh, don’t worry about the elephant by the way. The blunderbuss is for use on the next jackass who sits up excitedly during the scene where a dwarf in a tux wanders onscreen, and points and says “Look, it’s a dwarf! That’s a David Lynch moment!” I have five words for said jackass: Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen.

Granted, ‘My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done?’ – hereinafter, ‘My Son…’, since even the acronym treatment (‘MSMSWHYD’) is liable to give me RSI – starts out in startlingly non-Herzogian fashion with Detectives Havenhurst (Williem Dafoe) and Vargas (Michael Pena) shooting the shit in their cruiser as they head over to a murder scene. The deceased is a Mrs Macallam (Grace Zabriskie); the perp is her son, Brad (Michael Shannon). Brad has holed himself up across the road from the murder scene with a couple of hostages. A large chunk of the movie consists of Havenhurst and Vargas trying to open up a dialogue with Brad before the SWAT team open up a different kind of dialogue that involves hot lead.

In between attempts to appeal to Brad, Havenhurst and Vargas interview his girlfriend Ingrid (a winningly sympathetic Chloe Sevigny) and his erstwhile mentor, theatre director Lee Myers (Udo Kier). Brad’s increasingly fragile mental state is thus revealed in a series of flashbacks – some of which say more about the witnesses than about Brad – which document the months leading up to the murder. The first signs that he’d bummed a ride out of Normal, we learn, were after he returned from Peru. No sooner is this bit of dialogue out than we’re in Herzog territory good and proper, and to all the naysayers I offer this screengrab:

Of course, we were in Herzog territory all the time. The desperately self-delusive Brad is a man-child redolent of Bruno S. in ‘The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser’ and ‘Stroszek’. Herzog’s bleak vision of Americana in that latter film may have been upgraded from Wisconsin to San Diego in ‘My Son …’, but the same sense of dislocation, of alien-ness, remains. The dancing chicken at the end of ‘Stroszek’ finds is corollary in the flamingos that turn out to be Brad’s hostages.

The genius of Michael Shannon’s performance is the glimpse he gives us of the stunningly out-of-kilter way Brad’s mind works. You can easily imagine Brad sitting cross-legged in front of the TV for a Herzog marathon, favouring the crazed, messianic performances of Klaus Kinski in ‘Aguirre, Wrath of God’ and ‘Fitzcarraldo’ and fancying himself as America’s equivalent thespian talent. He’s an actor, is our Brad. Or at least he thinks he is. What we see of his rehearsals for Myers’s howlingly pretentious production of the Orestes tragedy is enough to convince otherwise.

Herzog throws out satirical barbs left, right and centre. ‘My Son …’ is poisoned love letter to a nation’s obsession with fame; a skit on actorly eccentricities (you can almost feel the ghost of Kinski hovering just offscreen); the most deadpan send up of cop movie conventions you’ll ever see; and an exercising in bouncing bizarro ensemble combinations off each and seeing what happens. Case in point? This scene …

… where Brad, already way up Bonkers Creek and demonstrably deficient in the paddle department, goes to borrow a sword from his jaw-droppingly racist and homophobic white trash ostrich-farmer uncle (Brad Dourif) while Myers camps in up in the background. Or the dinner table conversation which redefines awkward, where we have Shannon, Zabriski and Sevigny playing the scene as if it were written by Strindberg and directed by Mike Leigh and the two of them were at fisticuffs over how it should be played while their cast tried to do the take under a veil of abject embarrassment.

Did I mention that ‘My Son …’ is a weird little film?

Perhaps its weirdest element is its visual aesthetic. While images proliferate that could only have been conjured by Herzog, it looks uglier, muddier and less ecstatically poetic than is to be expected from a Herzog film. It was filmed using lightweight digital cameras, and while a whole generation of directors might have embraced the RED ONE, it pissed Herzog off no end. “An immature camera,” he declared, “created by computer people who do not have a sensibility or understanding for the value of high-precision mechanics which has a 200-year history.”

Fortunately, the film was created by a man whose understanding and values are at the other end of the spectrum. Oh, and it was produced David Lynch.

Thursday, 4 July 2013

This is the End

Okay. Imagine that Tarkovsky’s ‘The Sacrifice’ took place not in a remote dacha but a couple of miles from the Hollywood sign, that its protagonists were not a group of moody cerebral eastern Europeans but a cluster of egomaniacal actors, and that its coming apocalypse was signalled not by portentous reports on the radio but by the arrival of a Godzilla-sized demon with a penis of fire …

I’m not selling you on this, am I?

Okay. Remember when one of your mates first got a camcorder and a whole bunch of you decided you’d make a movie over the weekend only you put effort into drinking, smoking weed and arguing about what topping to order on your pizza than you did actually scripting the thing or worrying too much about blocking, camera-work, direction and, y’know, general coherence? And remember when you watched the resultant opus, some time later, stone cold sober, and realised it was an egregious embarrassment that ought never be seen by another human being? ‘This is the End’ is kind of like that, but made by celebrities and with a special effects budget. Oh, and there are actually some decent lines and a few scenes manage to land the occasional satirical punch, and …

I’m still not selling you on this, am I?

Hey, guys: for anyone who’s ever wanted to see Michael Cera impaled by a street light, Rihanna swallowed by a pit of fire, Emma Watson wielding an axe, and a bunch of over-privileged celebrities degenerate into full-on slanging matches over rights to a bar of Milky Way, the dividing up of a piece of cheese, and who jizzed on James Franco’s porno mag, then buddy THIS IS THE MOTHERFUCKING MOVIE FOR YOU!!!!

By the way, that splurge of capital letters and overdose of exclamation marks, hammered home with the expletive, is intended to introduce the reader, gently, into the brash aesthetic of the movie. The, ahem, plot involves Jay Baruchel, Seth Rogen, Craig Robinson, Jonah Hill and Danny McBride – all playing versions, spoofs or public perceptions of themselves, sometimes all of these things within the same, ahem, characterisation – converging at James Franco’s house for a party. Franco also plays a version of himself. Baruchel and Rogen nip down the block for a pack of smokes. The rapture happens. They freak out and head back to the party and ostensibly safety. However, the End of Days doesn’t give a flying fuck about their combined box office clout and hellfire rains down, a pit of fire ruins Franco’s lawn, and demons run amok. A small band of survivors scream at each other, run around and trade in sick humour for the next hour and a half. The overriding impression is that you wouldn’t want to hang out with them on a good day, let alone the Day of Judgement.

‘This is the End’ is bludgeoningly unsubtle, juvenile to the point of emotional retardation, and vulgar in a way that makes you wonder whether the script was actually written or simply assembled from a horrible alphabet soup created by sticking the spleens and bowels of Roy Chubby Brown, Andrew Dice Clay and Sam Kinison in a blender until various combinations of dick, piss and man-boob titty-fucking jokes bubbled up to the surface.

It should be utterly dire. It should be reprehensible. It should be the kind of film that earns a zero-word count on Agitation. And it is, at multiple points in its running time, all of these things. But it’s also genuinely funny and unexpectedly inventive at times. A running gag about a possible sequel to ‘Pineapple Express’ pays off in a sequel that recalls ‘Be Kind Rewind’, and there’s a send-up of ‘The Exorcist’ that is much much funnier than it has any right to be.

‘This is the End’ is not, by any set of critical perameters, a good movie. It’s not a movie I’d have any reason to watch again. But I laughed more often than not while I was watching it, and sometimes that’s all that’s needed.

Monday, 1 July 2013

What passes for normal service will resume shortly

Not that I've been in any way prolific on Agitation this year, but an unexpected technical problem means that my only current access to the tinterweb is via my phone. This is not ideal for blogging 800 word reviews. I'm expecting things to be resolved within the next week, and I've pieces planned on a certain animated comedy (hint: little yellow things proliferate) and one of Herzog's weirder offerings (which doesn't narrow it down quite so much!)

Friday, 28 June 2013

Sweetgrass

‘Sweetgrass’ drifts so far from the expected narrative or expositional tenets of the documentary format that it’s possible to forget you are actually watching a documentary and feel that, instead, you’re immersed in some kind of Tarkovskian art movie or film-poem.

‘Sweetgrass’ exists without narration or “talking heads” interview footage. For the first half hour at least, before a group of unnamed ranchers drive a sizeable herd of sheep through Montana’s Beartooth Mountains in search of pasture, barely a word is spoken. For the first half hour, the focus is entirely on the sheep. The ranchers float around on the periphery, but say barely anything. The camera insinuates itself amongst the herd and it seems for a while as if film-makers Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash are going to remain with the sheep’s POV for the duration – a prospect nowhere near as unappealing as it may sound.

Incidentally: the use of “filmmakers” in that last sentence. ‘Sweetgrass’ bears no director’s credit. It was produced by Barbash and “recorded” by Castaing-Taylor. The credits are as spare as anything else in the film, and it’s immediately apparent that’s exactly what Castaing-Taylor did: let he his camera record what was happening.

Ah, but there’s the rub. ‘Sweetgrass’ was shot between 2001 and 2003 (it wasn’t released till 2009) and two years’ worth of footage, even if collected intermittently, still leaves the editor with subjective choices in terms of sculpting a 105-minute feature which, notwithstanding its jettisoning of conventional narrative techniques, still needs a rhythm, a flow and an overarching structure. To put it another way: language is the least of Castaing-Taylor and Barbash’s concerns, but grammar still applies – the grammar of cinema. And every cut, as Truffaut pointed out … well, you know the rest. There’s also an eminently sneaky non-naturalistic moment involving the overdubbing of an extreme long shot with soundtrack that seems like it might have been “lifted” from elsewhere during the two-years Castaing-Taylor recorded the work of the ranchers.

It’s a measure of how successful ‘Sweetgrass’ is, however, that these considerations didn’t come to mind until way after those stripped-down end credits had taken up their minute and a half of screen time (if that) and this exhausted viewer was giving thanks that he doesn’t have to herd sheep for a living. Granted, there seemed to be a total dearth of the kind of office politics, lying, backstabbing, and rampant careerist arrogance that makes my place of work such a Machiavellian shithole, but at least I don’t have to deal with grizzly bears, dead sheep, vertiginous mountainsides, adverse weather conditions, 18-hour days, amenities that redefine basic, and loneliness that must seem all the more crushing for the grandeur of the mountains and the endless emptiness of the landscape.

Maybe it’s the loneliness that informs the scene I mentioned earlier; maybe all of the above. Over a shot that reveals itself as ever more magisterial the further the camera pulls back, the sheep diminished to almost unidentifiable white dots making a slow progress, en masse, up a steep gradient in the kind of landscape that inspires epithets like “wilderness country”, the ranch boss lets forth with an expletive-peppered rant against the sheep, his dogs and probably every single thing under the sun, using the word “fuck” so many times in just a couple of minutes that a mash-up of ‘Casino’, ‘The Boondock Saints’ and ‘In Bruges’ would have a hard time staying the course.

It’s a curious moment – it rams home the thanklessness of the work and the wearying reality of the conditions, but it also feels out of place in a film where there has been no music, no narration, and the sound design up to this point has been rigorously diegetic. But, as entered into evidence earlier in this review, this didn’t occur to me until afterwards. So maybe the proof is in whether an aesthetic decision intrudes enough to throw you out of the film while you’re watching it. Besides, the doctrine of Herzog’s “ecstatic truth” – an intellectually and aesthetically valid option for the serious documentarist – can be said to apply.

‘Sweetgrass’, ultimately, is an elegy for a way of life. The film is offered in memoriamthe very ranch it depicts: it ceased to be a going concern in 2004, just over a century after it was established. It depicts a way of life that was probably outdated several decades ago. There’s a scene of the ranch boss – a man of few words (when he’s not cussing, that is) and a chronic mumbler almost to the point of incoherence – is having a faltering conversation over a walky-talky. Between his linguistic deficiencies and a continual wash of static, it adds up to an awkward juxtaposition of the traditional and the contemporary. Remember Kirk Douglas riding across the scrubland in full cowboy gear in ‘Lonely are the Brave’, only to pull up his horse at the edge of a multi-lane freeway, huge Mack trucks thundering past? ‘Sweetgrass’ gives you that feeling for an hour and three quarters.

Friday, 21 June 2013

Excision

“Dear God, I have a lot on my plate at the moment: last week I had sex for the first time, my sister is slowly dying, and my mom – as I’m sure you know – is a total bitch.” Thus the prayer of sulky and socially inept teenager Pauline (Annalynne McCord). Prior to ‘Excision’, I was dimly aware that McCord was hugely popular in fuck-awful TV shows like ‘Nip, Tuck’ and the ‘90210’ reboot (and just typing “ ‘90201’ reboot” made me a little bit sick in my mouth). Post ‘Excision’, I have nothing but respect for the lady.

The objects of Pauline’s empathy and ire are, respectively, Grace (Ariel Winter) who is suffering from cystic fibrosis, and Phyllis (Traci Lords) who is suffering from being a stuck-up control freak suburbanite mom. Prior to ‘Excision’, I was dimly aware that Winter had done a hell of a lot of TV roles and been in ‘One Missed Call’, and was very significantly aware that Lords had a background in adult entertainment not to mention a shedload of equally exploitative B-movie roles. Both were infinitely better in this than I had any reason to expect.

In fact, I’ll go as far as saying that – with the exception of its somewhat abrupt ending – ‘Excision’ is one of the best horror movies I’ve seen in ages, and one of the best comedies. Note, I keep the categories separate. ‘Excision’ doesn’t slot into the comedy/horror subcategory as easily as, say, ‘Tremors’, ‘Slither’ or ‘Dale and Tucker vs Evil’. The comedic elements – and don’t let that trite little turn of phrase undersell it: this film is funny as fuck – are redolent of ‘Heathers’ or a nastier, less day-glo version of ‘Mean Girls’, while the horror tropes bring to mind the body horror of early Cronenberg infused with the in-yer-face grotesquery of Takeshi Miike or Kim Ki-Duk.

The set-up is basically an extrapolation of the interrelationships mentioned above. Pauline’s all-consuming love for her sister is the one constant by which she offsets being high school pariah, piggy-in-the-middle during her parents’ arguments, a lank-haired virgin, and dealing with an almost constant onslaught of cold sores which she blames on her father. His sin? Giving her mouth-to-mouth resuscitation after a swimming pool accident when she was younger. Pauline, in short has issues, and the film opens with the sublimation of her various psychological quirks into the dream state. It’s the first many dream sequences that punctuate the narrative, and they provide ‘Excision’ with most of its deliriously twisted iconography: dream sequences predicated on sexual imagery and clinical white backgrounds that generally don’t stay clinically white for very long. There’s also a lot of blood in Pauline’s dreams. Gallons of it.

But she’s not the kind of lass to dream her life away, is our Pauline. She quickly sets about resolving her issues. The virginity problem? Oh, look – there’s a football jock with an ice queen girlfriend who isn’t satiating his needs. Problem solved! (The payoff to this scene, channelling the imagery of Pauline’s dreams, will probably leave you feeling a little queasy.) The mom problem? A quick word with God: “Kill my mother. Kill her. You’ll probably want to make it painless. I get it – that’s your thing – but hear me out: a little pain never hurt anyone. And besides, you can always just blame it on the devil.” (Okay, jury’s still out on the efficacy of this method). Imminent death of beloved sister? Study to become a surgeon. Which is where Pauline encounters a couple of barriers: (i) timeframe, (ii) she’s a really crap student.

Can anyone guess where writer/director Richard Bates Jr is going with this? (And while you’re all jotting your answers on a postcard, let me take a moment to marvel at the serendipity of this fucked up little movie being directed by someone called Bates. Sometimes life is just priceless.)

‘Excision’ sets out its stall with such razor sharp efficiency (it clocks in at 81 minutes, five of which are the end credits) and sets up its denouement with such black-hearted delight that there are no real surprises on offer … except to wonder, as the sick jokes keep coming and McCord’s performance drills deeper and deeper into Pauline’s love-lacerated soul, just how far Bates and his anti-heroine can push things. And how they can possibly maintain the gallows humour.

The answer – without giving anything away – is that they know exactly when to cut off the laughing gas. ‘Excision’ is a body horror film with a surgery-obsessed protagonist. To use the obvious metaphor, once it’s finished operating on you, it doesn’t allow a gradual drifting awake in a recovery ward followed by a full clinical review before the ambulance carefully drives you home avoiding the potholes and speed bumps. No, siree. It stitches you up, tosses you back on the gurney like a sack of potatoes and sends you hurtling down the corridor, bashing through a fire door and out of the hospital, screaming.

Tuesday, 18 June 2013

Another thought on Now You See Me

Isla Fisher as a sexy escapologist? Check!

Really cool scene involving water tank, chains, padlocks and piranha? Check!

Major set piece later in the movie predicated on her escapology skills? D'oh!

Epic fail, all concerned; epic fail.

Monday, 17 June 2013

Now You See Me

Cineworld held a mystery film screening this evening, whipping up publicity by posting a series of downright oblique clues via Twitter. Messageboards were abuzz with speculation: many thought ‘Pacific Rim’, others plumbed for ‘The Lone Ranger’; when we booked the tickets, my wife was holding out for ‘The Wolverine’ while I had my fingers crossed for ‘The World’s End’. Ultimately, we were both disappointed. But at least it wasn’t two hours of CGI robots twatting aliens and then twatting each other. As we queued – interminably – I put a comment on FB to the effect that if it was ‘Pacific Rim’, I was going home.

We ended up not going home … well, not till the movie was over. We’d already agreed on the Half Hour Rule (if neither of us are digging a film at the half hour, we cut our losses and blow the joint). By minute thirty of ‘Now You See Me’, we were both enjoying it. By the time it was over, though, we had mixed feelings.

‘Now You See Me’ does several things right in very quick succession. It starts with a voiceover warning the audience that the closer they look, they less likely they’ll be to spot the trick. At the same time, a simple card trick plays out. The camera forces a very specific card on the viewer. It’s kind of a flipside to the opening of ‘The Prestige’. Where Christopher Nolan’s film clues you in to the three stages of an illusion, ‘Now You See Me’ deliberately sets out to obfuscate. It’s both a ballsy stroke of legerdemain and a self-defeating act: the longer ‘Now You See Me’ goes on, the more evident it is that director Louis Letterier wants his film to be a ‘Prestige’ for the Jerry Bruckheimer generation. But whereas ‘The Prestige’ has a genuine weighty human drama to anchor its more fanciful elements, ‘Now You See Me’ trades solely in the fanciful.

But let’s skip back to its opening reel. Having pulled a beautifully executed fast one on the audience, Letterier assembles his quartet of prestidigitatorial protagonists with superb economy, dealing out their vignettes like cards: street magician with a tendency to the theatrical J Daniel Atlas (Jesse Eisenberg), hypnotist/shakedown artist Merritt McKinney (Woody Harrelson), glamorous escapologist Henley Reeves (Isla Fisher), and new kid on the block Jack Wilder (Dave Franco). The narrative flings them together and has them pulled into the scheme of an unknown benefactor so quickly – the title card is a perfectly-timed punchline to the whole sequence – that their ineffably stupid names didn’t even begin to annoy me till a good halfway into the movie.

In equally quick succession, our foursome have been reimagined as a sell-out Vegas act who make headlines (and get themselves arrested) on account of an illusion based around a bank robbery. What pisses off the authorities, and gets Interpol newbie Alma Dray (Melanie Laurent) assigned to assisting rumpled sourpuss detective Dylan Rhodes (Mark Ruffalo) – this really is That Movie Where Really Talented People Play Really One-Dimension Characters With Really Stupid Names – is the disappearance of a fuckton of Euros from a Parisian bank that tallies exactly with the magic trick.

The rest of the movie – or at least, the 75% of it that conspires to make you take your eye off the ball prior to the big reveal – is essentially Dylan and Alma vs. The Four Horsemen (thus the collective name the illusionists bill themselves as, notwithstanding that one of them is a woman), while vengeful impresario Arthur Tressler (Michael Caine) and professional debunker Thaddeus Bradley (Morgan Freeman) hover in the wings nursing their own agendas.

‘Now You See Me’ is magnificently entertaining for a big chunk of its running time. Less than an hour in, I decided not to bother trying to second guess and just enjoy the ride. I’m glad I took that approach, because the whole improbably contrived plot pays off in a manner that, while not disappointing or in any way a cheat, is a little underwhelming. The essential problem with making a film about magic is that magic is a con. It’s smoke and mirrors; razzle dazzle; misdirection. It’s all surface and when you think about it too much, you dismiss it – rightly – as bullshit. ‘The Prestige’ is only superficially about magic – the real point of the film is the cost of the illusion; what you have to sacrifice to accomplish the seemingly impossible. To a lesser degree, Neil Burger’s ‘The Illusionist’ sets out its box of tricks as a backdrop to a tale of romance. ‘Now You See Me’ is entirely about the illusion, and as such starts to vaporise in a fog of its own insubstantiality the moment the end credits roll.

Sunday, 9 June 2013

The Iceman

Sometimes it’s the performance that makes a film. Off-the-top-of-the-head example: ‘Primal Fear’. An aesthetically redundant, narratively yawnsome courtroom drama transformed into something utterly watchable thanks to Ed Norton’s breakout role.

Notwithstanding that ‘The Iceman’ is an infinitely better crafted film than ‘Primal Fear’, much of it has the tang of the perfunctory while director Ariel Vromen never fully succeeds in engaging with the story’s key dynamic. Based on the true story (and if those words at the start of a movie don’t sound an alarm bell, then you’re probably a lot less jaded a film-goer than I) of hitman Richard Kuklinski, the story starts in 1964 with the inexpressive Kuklinski (Michael Shannon) having coffee with naïve girl-next-door Deborah Pellicotti (Winona Ryder, so not getting away with playing a twenty-something in these early scenes). Later, at a pool game, an acquaintance refuses to pay Kuklinski off over a bet then compounds the offence by making ugly remarks about Deborah. For which he ends up with his throat cut in an alleyway. Shannon plays this pivotal moment to perfection: there’s a moment when he genuinely convinces you – never mind that you’ve just shelled out for a ticket to see him playing one of the most notorious contract killers of his time – that Kuklinski might just let it go and walk away. And when he does walk away, albeit after effecting a straight-razor/jugular interface, the sense of dispassion is shattering. It’s one of a handful of moments where Vromen absolutely nails the tone he’s looking for. He’s not quite so successful elsewhere, though.

Jump forward a couple of years – the first of numerous and often inelegant lurches through a two-decade timeline – and Kuklinski and Deborah are married, with a baby daughter and looking to better themselves. Kuklinski’s working on the periphery of the criminal underworld, cutting film and delivering prints for a low-rent pornographer. A disagreement over a delivery date spins him into the orbit of mob boss Roy Demeo (Ray Liotta). Impressed by how little fear/emotion/give-a-shitness Kuklinski evinces in the face of his goons, Demeo hires him on the understanding that he works for no-one else. Kuklinski takes to the work like a duck to the proverbial. He doesn’t seem to relish killing, but it doesn’t bother him either. It’s just something that he happens to be very good act. Dude loves his family – “You and the girls,” he tells Deborah during the closest he comes to an emotionally-charged scene, “are the only thing I care about in this world” – but as far as the rest of humanity is concerned, he’s utterly cold. Ergo, the iceman.

After a brutally effective Kuklinski-straight-up-kills-a-fuckton-of-people montage, Vromen gets bogged down in the minutiae of underworld politics, mob hierarchy paranoia, rivalry, betrayal and bad decisions. It’s the kind of milieu that Scorsese or Coppola would sail through, sketching out the interrelationships and knife-edge tensions in a scintillating whirl of exposition of set-piece. Vromen isn’t quite in their league and there’s a palpable sense, as events snowball in the largely 70s-set mid-section, of the script stumbling and gasping for breath as it tries to keep up with everything. By now, Demeo’s fuck-up of a right hand man Josh Rosenthal (an almost unrecognisable David Schwimmer) has incurred the ire of another outfit whose consigliore Leonard Marks (Robert Davi) is putting pressure on Demeo to cut the kid loose (in the terminal sense of the word); Demeo’s pissed off at Kuklinski for not killing a witness (a 17 year old girl – his daughters are by now teenagers themselves); and Kuklinski, essentially unemployed, has teamed up with ice-cream van driving hippie assassin Mr Freezy (an equally unrecognisable Chris Evans) to pull in enough money to keep his family in the style to which they have become accustomed. Oh, and there’s also some business about Kuklinski’s nutcase brother Joey (Stephen Dorff), in prison for killing a young girl.

Buried in all of this is the film that the tagline on the poster – “loving husband, devoted father, ruthless killer” – hints at. Because here’s the fascinating thing: when the Feds arrested him after an undercover agent netted him in a classic bit of entrapment, his family genuinely had no idea that he was a mob-employed enforcer who had killed over 100 people. No idea. And if the mechanics of how an essentially amoral hitman not only kept work and home life separate but maintained a façade of domestic normality for two decades isn’t a great concept for a movie then I don’t know what is.

Unfortunately, Vromen is too busy leaping through the chronology (not that the film even considers the real Kuklinski’s already notable criminal activities during the 50s and his association with the DeCavalcante crime family that pre-dated his involvement with Demeo) to focus on this aspect. The script throws out a few lines about Deborah thinking that he works in investment banking, and the whole family man persona is dramatised by means of his daughters hero-worshipping him (why they venerate him is never contextualised).

So why – with the mission statement of this blog being the love, not the criticism, of film – am I spewing 1,000 words on ‘The Iceman’? Three reasons, really. Firstly, its emulation of slow-burn 70s filmmaking is a welcome respite from the flashy tentpole nonsense that has dominated the screens of my local multiplex recently. Secondly, it looks great: akin to Roger Donaldson’s ‘The Bank Job’ and Tomas Alfredson’s ‘Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy’, it’s a film predominantly set in the 70s that both looks and feels like it was made in the 70s. Thirdly, the performances. There’s an entire cluster of great performances, with Shannon’s towering slab of subdued greatness at the centre. Liotta, in a career based on casting directors exploiting his iconic role in ‘Goodfellas’, is as engaged as I’ve seen him since that movie. Sure, he’s doing the same old gimlet-eyed Liotta shtick, but here it seems authentically dangerous. Davi does his best work for a couple of decades, and Schwimmer and Evans physically lose themselves in their characters in a way I would never have anticipated from either of them.

Monday, 3 June 2013

Populaire

On the bus home from the cinema earlier this evening, I shared this little nugget on Facebook:

“Populaire: enjoyably cheesy feel good typewriter porn. And that’s not a sentence I envisaged writing when I got up this morning!”

The above functions as a reasonable enough capsule review. Here’s the more considered version:

Populaire is the kind of film that, if I got made in Hollywood – okay, so a Hollywood studio greenlighting a romcom set in the high-stakes world of typing competitions is a tad unlikely, but bear with me here – would star Katherine Heigl as the ditzy but gorgeous typist and Gerard Butler as the smarmy failed-athlete-turned-businessman who sees her as a ticket to exonerating his lack of competitive edge way back when. There would be training montages, awkward banter that pirouettes gradually into the suggestive, and an all-or-nothing finale on the eve of the world championship competition. All of which, to be fair, can be found in the non-Hollywood Populaire that exists here in the real world, directed by Regis Roinsard and starring Deborah Francois and Romain Duris. The difference is that Hollywood would meld this material into a tame romantic comedy with no real stakes and the typing just a quirky backdrop to the boy-meets-girl predictability.

Populaire takes its typing seriously. The various tournaments Rose (Francois) competes in are depicted either as endurance tests (one in particular comes across as They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? with typewriters instead of dancing) or outright duels. At one point, Roinsard whips the camera back and forth between the blurred fingers of two finalists, the motion suggesting a tennis match.

Nor are the romcom elements necessarily tame, no matter how much the swirling, pastel-coloured stylisations of the first half might conspire to kid you otherwise. The sexual tension between Rose and the sullen, driven Louis (Duris) resolves in what the BBFC guidance text calls “one moderate sex scene”, as a prelude to which the protagonists have a toe-to-toe argument and treat each other to a good hard slap before they get en sac.

This is a good place to consider Populaire’s unreconstructed worldview, and to make a tip of the hat to Roinsard for utterly nailing the aesthetic. The film is set in 1959 – it has to be, given the subject matter and the development in typewriter technology that it pays off with – and it both looks and feels like it. There’s a casual sexism that was pretty much the norm in cinema (and literature … and, hell, in society itself) in the 50s and 60s. It’s there in the parade of wannabe secretaries vying for a job with Louis. It’s there in the man-hungry vamp who practically throws herself at a coolly unresponsive Louis in a bar. It’s there in the sneering, leering mambo singer who practically oozes his performance at a smoky club.

Fortunately, all of this is balanced by the sheer irresistibility of Francois’s performance. (The most likeable heroine French cinema has given us since Amelie Poulain? I’m calling it!) It’s balanced by a cluster of hilarious moments, from an impromptu dance sequence to Rose’s colour coded nail varnish, an aid to touch typing.

Narratively, Populaireoffers no surprises. It reminded me of Papadopoulos and Sons in its use of tried-and-trusted plot points: with the story taking care of itself, the script is free to investigate the oddball psychological struggle between Louis’s need to compete and his fear of fulfilment, as well as the familial underpinnings to Rose’s inveterate clumsiness and lack of confidence. The baby boom materialism of the late 50s – highlighted by the presence of expatriate American Bob (Shaun Benson) as Louis’s rival-cum-friend – makes for an effective counterpoint to the human story.

Populaire isn’t perfect – Louis’s recollections of his wartime past as a member of the Resistance freight the script with something entirely at odds with everything else in the film, and there’s some cringeworthy national stereotyping going on in the world championship sequence – but it makes for an entirely entertaining and just-quirky-enough two hours at the cinema, its ostensible superficialities masking a well-crafted grown-up piece of filmmaking. An excellent choice for the discerning populist.

Thursday, 16 May 2013

Danny Trejo

This is how you cut a birthday cake!

Happy 69th to Danny Trejo. I can't frickin' wait for 'Machete Kills'.

Tuesday, 14 May 2013

Into Darkness We Trek (guest review by Mark Poole)

Look, I’m a Trekkie, I have been and ever shall be a Trekkie (Trekkies will see what I did there). I’m not a Trekker. What’s the difference, you ask? Well, there are a lot of definitions, but mine is this: a Trekkie is a light hearted diehard fan who enjoys the ‘Star Trek’ franchise for what it is; good solid entertainment. A Trekker is the kind of fan who questions everything about the franchise, such as going to conventions and instead of thanking the actors who have appeared in the shows over the years, they question why in certain episodes the said actor pressed a certain button on a certain computer panel. You see the difference? Good! Where am I going with this you ask? Well, bear with me for a little while longer …

These days it’s Chic to be Geek, and I’m a Geek. Although I have never had sand kicked in my face (I’d like to see someone try), I have had to put up with the usual crap that comes with being a Geek. Until now; the current upturn for sci-fi demands that Hollywood make things cooler. And they don’t get cooler than J J Abrams’s ‘Star Trek’ films. The first one not only established new actors in old familiar roles, but also showed us how these characters came to be. We had Kirk, Spock and McCoy all enrol in to Starfleet Academy. We see how they became the great heroes we admire and love. We see the U.S.S. Enterprise on her maiden voyage, already knowing that this ship and crew will be best and brightest of the United Federation of Planets.

So now we’ve got the first film out of the way, it’s time for the sequel! And this film is so much bigger than the first! IT IS HUGE! But does it make it better? Short answer: Yes… Long answer: No… Confused?... Yes?... So was I, until I sat down to write this review. You see, there are certain events that I can’t discuss without revealing spoilers. So it’s really hard to say where the problems lie. So to explain how, let me take you back to 1982; the film is ‘Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan’. This film is arguably the best of the original Trek films. The crew of the Enterprise is pitted against the villainous Khan played deliciously by Ricardo Montalbán. In the penultimate scene, Spock sacrifices his life to save the Enterprise from certain doom (anyone who says spoilers about a 1982 film, I have my phaser set to stun). While Spock lies dying Kirk is told to hurry down to engineering to see his fallen comrade. The emotion of this scene is raw and beautiful; it’s hard not to shed a tear, Kirk and Spock brothers in arms unable to touch through a glass wall, Kirk unable to save his best friend from the radiation that runs through Spock’s body. I defy anyone to say that this scene was not a fantastic moment in Trek history!

Fast forward to 2013 and ‘Star Trek: Into Darkness’. This film, as great as it is with its fantastic special effects and gripping story line, lacks the emotional depth, or soul as my better half put it. So whose fault is it? Well … it’s certainly not J J Abrams’ and it’s undoubtedly not the actors - Chris Pine and Zachary Quinto excel as Kirk and Spock, as do the rest of the cast. Having said that, the rest of the cast are used sparingly and most of the time it’s just for comic relief, especially McCoy who in the original Trek films was the emotional counterpart to Spock’s logic. I can’t help thinking that downplaying McCoy as they did was a very bad decision, seeing as Karl Urban’s McCoy was by far my favourite character in the previous film. The antagonist of the piece is played by Benedict Cumberbatch of Sherlock fame, who in my eyes is a fantastic actor but seems to be very two dimensional in a three dimensional movie.

But I think the fault lies with the writers, it seems they started well but couldn’t be bothered to finish the story properly! It lacks originality, which is truly a shame. If they had taken the time to be more unique, this film would have seriously been off the chart! This brings me back to Trekkies vs Trekkers, if you are truly a Trekkie or have no Trek knowledge whatsoever you will love this movie. But if you are a Trekker, well ... don’t say I didn’t tell you so!

So what’s next for the crew of the Enterprise? Abrams is off to do another ‘Star’ movie, but it’s of the ‘Wars’ and not the ‘Trek’. Will he return to the franchise? Who knows? But if he does I will be there to welcome him with open arms.

Friday, 10 May 2013

In brief: Cave of Forgotten Dreams

There’s a scene in ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ where the screen is filled with a computer-mapped image of the interior of Chauvet Cave in southern France – home to a veritable art gallery’s worth of pre-historic cave paintings – while Herzog delivers an unusually ordinary bit of expository voiceover. Cut to one of the technicians responsible for the mapping, sitting at a desk, computer in front of him, discussing the mapping work. Again, it’s all very typical of a documentary opening with the History Channel’s logo. Then the technician happens to mention that he comes from a non-scientific background; Herzog interrupts him and asks what he did before; the man gives a self-conscious grin and answers that he was in the circus. And – bingo! – we’re in Herzog territory good and proper.

While ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ – haunting music and dream-like meditations on the unknowable past notwithstanding – is one of the more orthodox entries on Herzog’s CV, it’s still the kind of film that only Herzog could have made. The chance to film, in strictly regimented conditions and with an almost draconian time limit, an area that will never been seen except by a handful of scientific experts must have been irresistible to modern cinema’s most passionate explorer. The historic importance of the paintings was established very shortly after their discovery in 1994 and the cave was immediately sealed off. Restrictions around access were imposed to preserve the cave’s climate and conditions. Herzog and a crew of just three had to use battery powered equipment and use lighting which gave off no heat.

Sure, it’s not as crazy as the “hey, there’s a small island that might just get blown to shit by an active volcano, why not let’s fly in?” aesthetic of ‘La Soufriere’, but there’s that same sense of race-against-time filmmaking at work. Oh yeah, and he shot it in 3-D as well. (Full disclosure/bone of contention: ‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ came and went in Nottingham cinemas in something slightly faster than the blink of an eye. I’ve only seen it on DVD in bog standard 2D. It still rankles that I didn’t get to see it on the big screen and in the original format. I think it would have proved cinema’s only genuinely tactile use of the form.)

‘Cave of Forgotten Dreams’ is several things – the least of which is a documentary about cave paintings. It’s about memory, perception, dreams, and the passing of time. And it’s an act of liberation. It takes the sealed Chauvet cave, wrests it from the hands of researchers and academics, and makes a beautiful and richly textured gift of it to the world.